Historians such as Harvey Khler and Beverly Tomek argue (respectively) that “self-determination…as a practical matter was all but irrelevant”(23) and that the Black Belt Thesis “failed to gain traction beyond a small group of intellectuals within the Communist Party” (24). While honest-faith criticisms of the Party are necessary, these claims undermine the role that Black communist scholars and union members played in adopting and creating an ideological lens through which to understand their exploitation. The narrative that the Black Belt Thesis was a hazy theoretical concept beyond the scope of the SCU’s members is not only incorrect but also rooted in racist and classist assumptions about Black tenant farmers. If the SCU was reading about Lenin and Nat Turner and holding rallies against Hitler’s new government, it is safe to say they were immersed in political theory, history, and current events. And after all, what is so difficult to comprehend about Black people having the right to determine their political destinies in a region where they were the majority? (25)

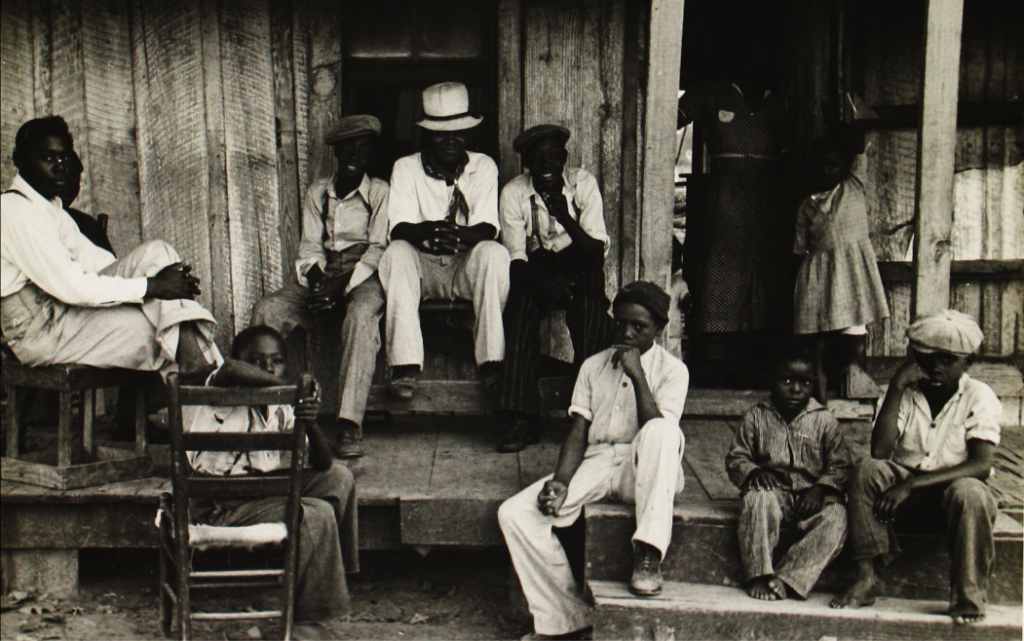

By 1934 – only three years after its founding – the SCU reported more than 6,000 members. The rapid increase in union participation was a result of mass evictions and landlord abuses stemming from the New Deal Agricultural Adjustment Administration (26). The SCU built enough power to increase wages, protect tenants from evictions, and collectively bargain with landlords using strikes. When Harry Haywood attended an SCU meeting, he was surprised to see a small arsenal: “there were guns of all kinds—shotguns, rifles and pistols. Sharecroppers were coming to the meeting armed and left their guns with their coats when they came in” (27). Without arming themselves against the landowners, local authorities, and vigilante violence, the founding SCU members would never have survived let alone built a powerful union. The material assistance from the CPUSA and the ideological backing of the Comintern was undoubtedly essential in the SCU’s fight for freedom. In conclusion, the sharecroppers of Alabama used a Marxist-Leninist analysis and a militant self-defense strategy to build union power and fight against racism and class exploitation in the Black Belt.

Notes

(23) Klehr, 327.

(24) Tomek, 549–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/wusa.12004.

(25) Johnson, Timothy V. “‘We Are Illegal Here’: The Communist Party, Self-Determination and the Alabama Sharecroppers Union.” Science & Society 75, no. 4 (2011): 454–79. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41290188.

(26) Kelley, 54.

(27) Kelley, 45.