The Communist Party responded to calls for organizing from sharecroppers and helped them to arm themselves and form a union. In 1930, communists organizing in Birmingham were largely disconnected from the more isolated, rural sections of the Black Belt. In January of 1931, five hundred sharecroppers in England, Arkansas engaged in uprisings against the poverty and destitution they were facing (10). The Southern Worker encouraged poor farmers in Alabama to do the same, and they received an influx of letters from sharecroppers asking for help organizing. One tenant wrote:

We farmers in Vincent wish to know more about the Communist Party, an organization that fights for all farmers. And also to learn us how to fight for better conditions.

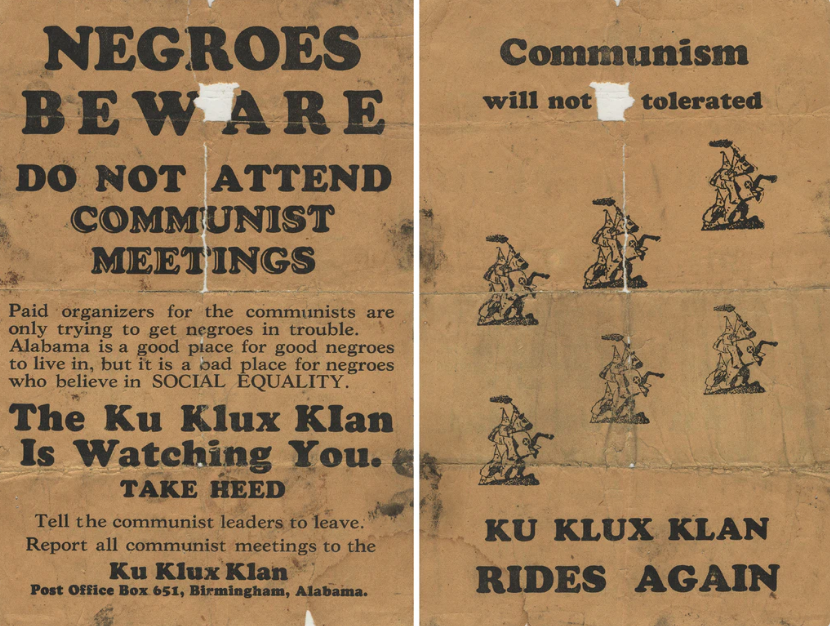

Another said that he planned to “get a bunch together for a meeting” because the poor farmers in his community were “mighty close to the breaking point” (11). Black communist organizer Angelo Herndon visited Wilcox County to help a group of sharecroppers who were meeting with their minister to form a union, but he was threatened by the police and forced to flee (12). In Tallapoosa, a majority Black county, a young school teacher and daughter of a militant anti-racist sharecropper family began secretly distributing Southern Worker. Members of the community invited a Party organizer to help them unionize. At a Tallapoosa rally to free the Scottsboro Boys in 1931, a white mob lynched five sharecroppers and wounded more in what came to be called the Camp Hill Massacre. The police stood idle as white mobs called to “kill every member of the Reds there and throw them into the creek,” and spent days attacking dozens of Black families, forcing them to seek shelter in the woods (13). Despite this constant, ever-increasing onslaught of state-sanctioned violence and white supremacist police and mob rule, sharecroppers and Party organizers were not deterred in their struggle to form a union.

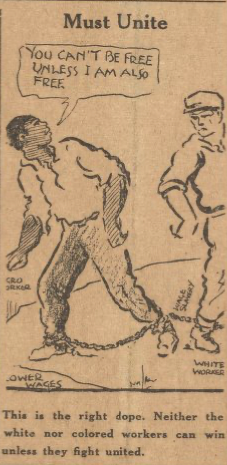

The Alabama Sharecroppers Union (SCU) merged their day-to-day organizing efforts with a Marxist-Leninist analysis. By 1931, the SCU had upwards of fifty members and was fully operating on its own without the influence of the Party, who they kept updated with the help of a liaison. The sharecroppers were “carrying on the work on their own initiative even [though] we have not sent an organizer down there” (14). By 1932 thanks to the efforts of a nineteen-year-old Black woman organizer named Eula Gray, there were 591 members organized in locals, youth groups, and women’s auxiliaries. Al Murphy was the SCU’s next secretary, and he bolstered the union’s militancy and security. Murphy was a strong supporter of Black self-determination, and he shaped the union around this long-term goal. A few poor white sharecroppers joined meetings, but Murphy was insistent that their solidarity was only useful if they were eager to unite under Black leadership. Many whites offered food, supplies, and cover to the SCU, and one white man was lynched in 1934 for showing his support publicly (15).

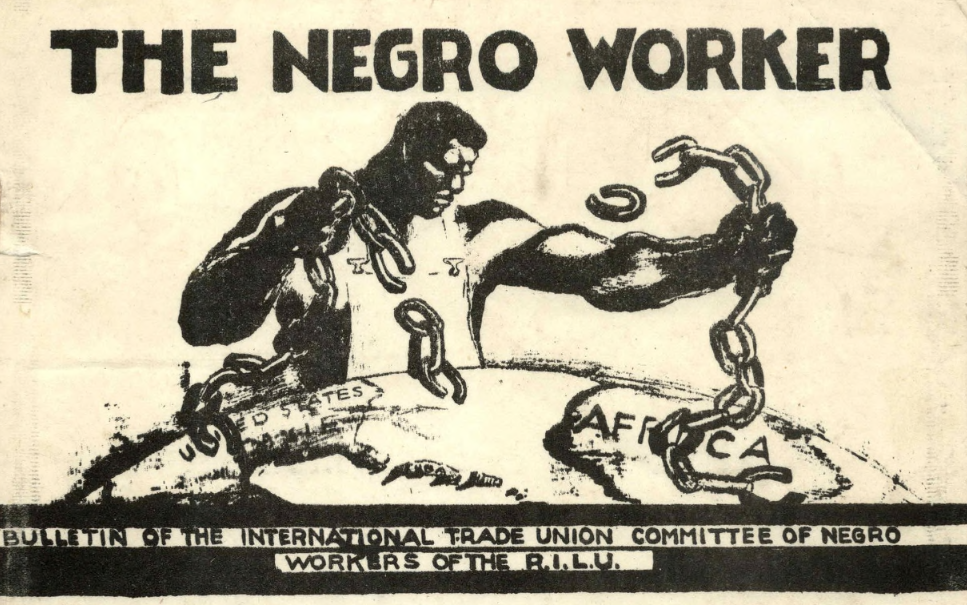

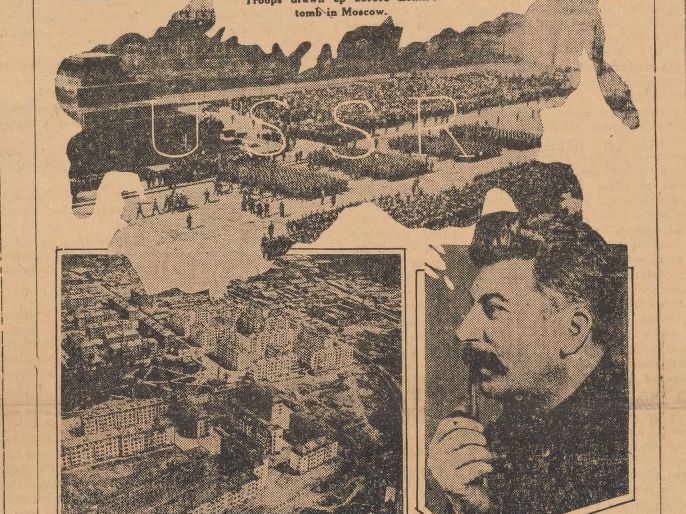

Sharecroppers did not keep written records of their meetings or activities to protect themselves from criminal conviction, but we can infer the content of their meetings from the public actions they pursued––such as arming themselves for self-defense against the landlords and white mobs. Women’s auxiliaries held considerable power in the union, and they were responsible for writing to outside Parties, individuals, and communist newspapers. The women often met under the pretense of “sewing club” to read Southern Worker, the Daily Worker, and Working Woman. While educating themselves on Marxist-feminism that spoke to their everyday concerns, these women condemned male chauvinism; men began taking care of the children during the “sewing club” meetings (16). Sharecroppers were heavily influenced by communist newspapers, works by Lenin, Marx, Stalin, and American Marxist works such as James Allen’s Negro Liberation. This literature was illegal and if found in possession of it, a sharecropper could be arrested, attacked, or lynched. In the SCU study groups, communist literature was read aloud and the members discussed the work’s relevance to their own lives. Reading theory allowed people living in geographic isolation without access to formal education a way to understand their struggles as a part of a bigger global movement. For example, when German Communist leader Ernst Thaelmann was jailed by the Nazi regime in 1933, Eula Gray organized a mass rally in protest of Nazism and the SCU dispersed hundreds of anti-fascist leaflets throughout Tallapoosa County (17). Although most of the SCU’s demands centered on immediate improvements like higher wages and debt forgiveness, they also identified as part of the larger Communist movement and were invested in building a revolution.

Marxist theory worked in tandem with the sharecroppers’ experiences to determine how they resisted their oppression. As Robin Kelley argues, Black communists were not “blank slates” when they entered the movement: “they were born and reared in communities with a rich culture of opposition—a culture that enveloped and transformed the Party into a movement more reflective of African-American radical traditions than anything else” (18). There has been an anti-Black narrative among communists and liberals alike that sharecroppers learned a Marxist-Leninist analysis and the importance of Black political power from the Northern communists who came to the rescue, and not the other way around. As any Marxist should understand, theory is not a prophecy but an observation of the class struggle that already exists––and the Black national question is no exception. Black Belt communists may have learned Lenin’s name from the Party publications, but the farmers had been battling against the same fundamental exploitation which Lenin wrote about for the entirety of their lives. In other words, Marxist theory did not teach Black farmers how to resist––it gave them new tools to understand their historical oppression through the lens of the global capitalist political economy and the subjugation of the Black nation. Lemon Johnson, former member of the SCU, was asked in 1986 how the union was able to succeed. “Without the slightest hesitation,” Johnson “pulled out a dog-eared copy of V. I. Lenin’s What Is to Be Done and a box of shotgun shells” and said “‘Right thar, theory and practice. That’s how we did it. Theory and practice’” (19).

A Marxist-Leninist analysis was fundamental to the SCU’s successes because it granted a concrete path to liberation that no other political movement could offer at the time. After a shoot-out in nearby Reeltown left several sharecroppers dead and untold dozens wounded while the SCU defended a Black farmer from eviction, white liberals published their disdain for the SCU:

It is the ignorance of the negro which makes him prey to the incendiary [communist] literature with which the mail boxes of both white and negro farmers of Tallapoosa County have been stuffed. It is this literature which transforms him from a law abiding citizen into one who defies the law. . . The average negro in his normal state of mind does not consider firing on officers seeking to carry out the law (20).

Several anti-communist Black reformists from the Tuskegee Institute and the NAACP echoed these sentiments, offering sympathies to the sharecroppers but failing to support the union and arguing that Black people should “battle for our rights legally in the courts, and economically through mass-owned businesses” (21). This statement is particularly shocking because it ignores the neo-fascist political landscape in the Black Belt. A sharecropper could be attacked or lynched for simply begging a landowner for better wages. The idea that Black tenant farmers could successfully fight for their rights in a court of law was ludicrous for various reasons: they were disenfranchised, barred from receiving a quality education, and the court system was systematically designed to ensure white-serving outcomes. Birmingham detective J.T. Moser demonstrated these fascist politics in 1934 when he said:

We ought to handle you reds like Mussolini does ’em in Italy—take you out and shoot you against the wall. And I sure would like to have the pleasure of doing it (22).

Just as the Communist Party’s previous “class before race” strategy had failed to address the severity of Black national oppression in the deep South, the political line of the Black capitalists and reformists left the poorest most exploited Black farmers behind. In response, the SCU forged a new path of Black communist militancy that ideologically challenged white Party members and was unacceptable to most whites and some Black middle-class liberals.

Notes

(14) Kelley, 43.

(15) Kelley, 48.

(16) Kelley, 46.

(17) Kelley, 98.

(18) Kelley, 99.

(19) Kelley, XV.

(20) Kelley, 52.

(21) Ibid.

(22) Kelley, 57.